A Rendezvous With Mrs Phoola Warikoo

Team ISBUND met (virtually) with Phoola ji to chat about Herath festivities with her and relive her memories of celebrations in Kashmir when she was a little kid. A brief excerpt of our long chat is here. Herath poshte to all!

Take me back to the days of Herath in Kashmir? What was your favourite part?

Back in the days when we were young kids in Kashmir, life was not as easy as it is today. Electricity was limited, winters were harsh and there were no electrical appliances or home help to make life easy. Herath, therefore, was a time when the entire household spent days cleaning up every nook and corner of the house, washing all those heavy winter clothing, and generally sprucing up the entire homes.Children of the household played with cowries ‘Harre’ while the elders were busy with Herath preparation. I have very fond memories of those days playing with cowries.

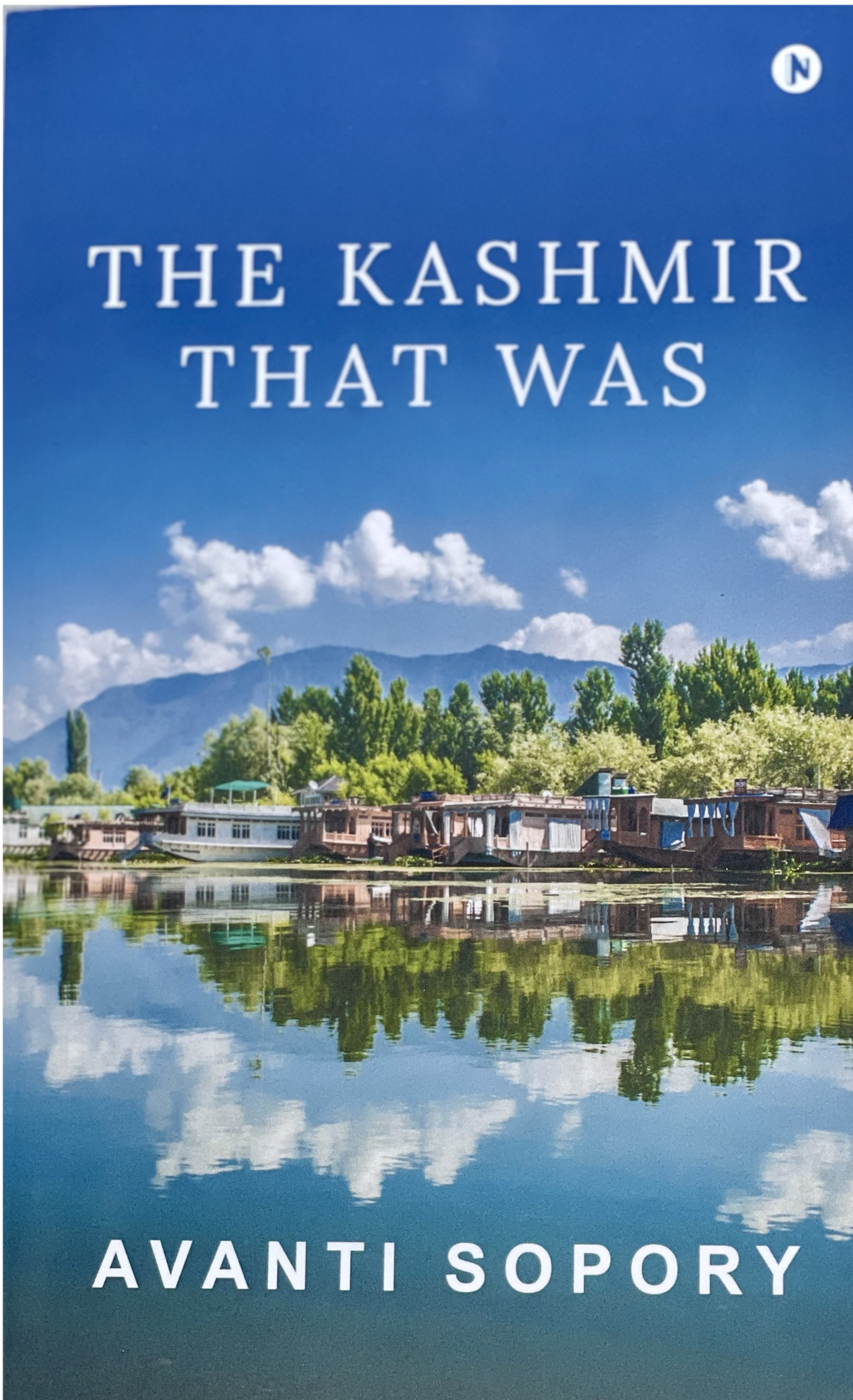

Our Herath or Shivratri as it is mostly known outside of Kashmir is strikingly different, more elaborate, more festive, a perfect combination of devotion and festive. One thing that is very prominent is the ritual of ‘vatuk barun’. I have vivid memories of sitting by my grandfather’s side while he got the elaborate vatuk set up. For those of us who never experienced this tradition first-hand in Kashmir or even outside, what does it entail and what is its significance?

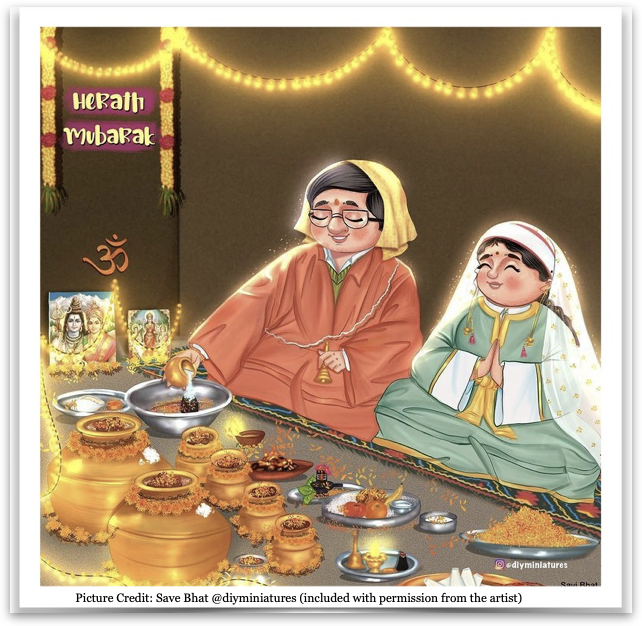

On the day of Vatuk barun, the ladies of the household were busy preparing the many dishes which would be offered to Lord Shiva. The setting up of Vatuk and getting puza materials ready was an elaborate affair. In many households, the family priest ‘Guruji’ would arrive and complete the puja. As he used to be a very busy man on the day, needing to attend many houses, his puja would be a quick one, lasting no more than an hour. In our home, it took much longer and was conducted by my father and his three brothers. The men of the house used to fast until after the puja had completed. The children would be up way past midnight, enjoying the food, playing with cowries and generally having fun.

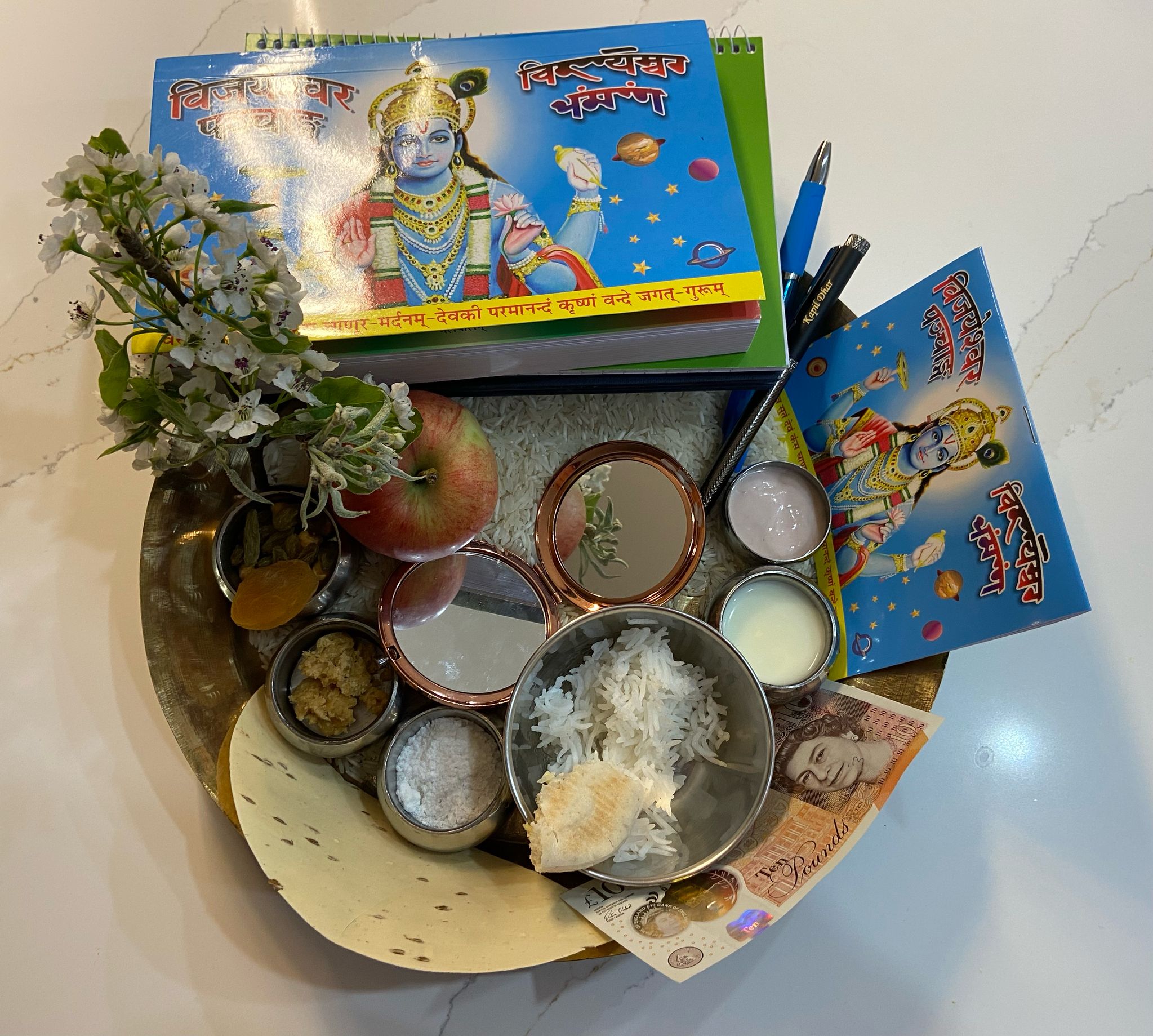

Shivrati is considered a celebration of the union of Shiva and Shakti. The vatuk set up in essence depicts the marriage party of Lord Shiva. The Vatuk comprises of a large earthen or metallic pot which represents Lord Shiva, a smaller pot representing Ma Parvati, 3 Sanivaris, Sanepatul, 3 Rishi Duljis, Dhupazoor etc. representing Shiva’s dwarpals, and baratis. The pots are filled with walnuts and fresh water and decorated with marigold flowers and placed on mats made from grass.

Growing up I have always wondered why some Kashmiri families didn’t partake in celebrating with others. I understand these families, called Gurit follow different rituals for Herath. Please may you help explain what the differences are and how they celebrate it?

Gurit families were mostly Kak’s or Razdans. They generally do not cook meat or fish during the festival and do not visit other families. They used to cook daal with nadur and dumaloo, the daal tasted so divine that people will forget their roganjosh. Some Gurit families used to prepare fish on Doon mavas but it is not a tradition followed by all.

Why do we call Shivratri ‘Herath’ and why the day that follows is called ‘Salaam’. Can you tell us a little more about it?

There is a story that reflects our belief in Shivratri and the power of Lord Shiva. It is said that a ruler of Kashmir known as Jabar Khan was so annoyed with this deep rooted faith that he ordered Pandits to celebrate Shivratri in July instead of the Phalgun season. As they didn’t have a choice, they assented. To everyone’s surprise, that day in July when Pandits celebrated Shivratri, it snowed. People were not happy with the ruler as their crops were destroyed and livelihoods were lost. Muslim neighbours, therefore, came visiting the following day offering their ‘Salaam’ to acknowledge this unseen power of Lord Shiva. Since this event surprised (‘Hairat’) everyone, the festival was thereafter, also referred to as Herath and the day when Muslim friends came visiting is popularly known as ‘Salaam’. The ruler was also given a new nickname ‘Jabar-Janda’ and the saying goes… ‘Jabar Janda Haras auw vande’ meaning winter came in July because of the rag man Jabar.

Salaam festivities has its own variations across families with the food differences. How did your spread look like?

All families follow a set of rituals that were started many generations before them. On the day of vatuk barun, most Pandits offer a vegetarian spread but on Salaam, the spread is mostly non-vegetarian featuring Roganjosh, matsch, dumaloo, nadru etc.

Doon mavas, we have this lovely sequence we say when we get the vatuk back into the house, what is its significance.

The 15th day of Phalgun is known as ‘Doon Mavas’. On this day, the water (nirmaal) from all the pots from vatuk is drained out and immersed in the nearby river or well or under the trees. The walnuts are washed and brought back home. When the party arrives home from the river, they knock at the door and announce that they have brought ‘ann’ and ‘dhan’ (food and wealth) with them and are welcomed inside.

The walnuts and rice pancakes are offered as ‘Naveed’ to everyone and distributed among neighbours and relatives.

The first Herath after marriage has its own festivities attached with the girls parents sending gifts with walnuts to her house. Her in-laws would then distribute these walnuts and bread among their own relatives and neighbours.

What do you miss the most, and how is you Herath different now?

I miss celebrating Herath with the extended family the most. But I am happy to celebrate it with my son and his family, passing on the tradition to them and imparting this knowledge of culture that I have to my granddaughter. We don’t get all the samigiri we need, like ‘bael patir’ for the puja here but it doesn’t matter. You need to offer your prayers with shraddha and that is all that matters. May Lord Shiva bless you all.